Bettina Bien Greaves was born in Washington, D.C. During World War II, she worked for the U.S. government’s Foreign Economic Administration in South America (La Paz, Bolivia) and in Europe (Vienna, Austria).

At that time she knew nothing about the Austrian School of Economics, but she has revisited Vienna several times since to research the life and works of Ludwig von Mises, with whom she later studied and came to know. Her serious study of economics and of the free market economy started in 1951 when she joined the staff of the Foundation for Economic Education in Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y., and enrolled in Mises’ economic seminar at New York University, which she attended regularly until Mises’ retirement in the spring of 1969.

She worked at the Foundation for more than forty years, was appointed Resident Scholar in 1992 and then retired in 1999 to live in North Carolina.. She has finished editing the manuscript of her late husband, Percy L. Greaves, Jr., who died in 1984: The Seeds and Fruits of Infamy: The Background, Investigations and Cover-up of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor and is currently in the process of cutting it in preparation for publication.

Mrs. Greaves authored an economics syllabus for high school teachers, Free Market Economics: A Syllabus (1975) and assembled for students an accompanying Basic Reader. She translated from the German several works by Mises on monetary theory which were published in English as On the Manipulation of Money and Credit (1978). She has compiled or edited several works: a collection of articles by Ludwig von Mises, Economic Freedom and Free Enterprise (1990), a collection of papers by early “Austrian economists,” Austrian Economics: an Anthology (1996), an unpublished 1940 manuscript found among Mises’ papers, Interventionism: An Economic Analysis, and an abridgement published in 1999 as Rules for Living: The Ethics of Social Cooperation consisting of several chapters from Henry Hazlitt’s 1959 work, The Foundations of Morality. Mrs. Greaves also compiled Mises: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles By and About Ludwig von Mises (Volume I, through 1981, the 100th anniversary of Mises’ birth, published 1993, and the update Volume II, 1982-1993, published 1995). For six years, Mrs. Greaves taught economics at the New York Institute of Credit in New York City. She has lectured widely in the United States, also in Guatemala, Mexico, France, Poland, Finland, the Czech Republic and Romania. Mrs. Greaves, together with her husband the late Percy L. Greaves, Jr., was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Universidad Francisco Marroquín in Guatemala (Central America). She kindly answered these questions after her 1994 visit to Romania:

Q & A on Mises and the Austrian School

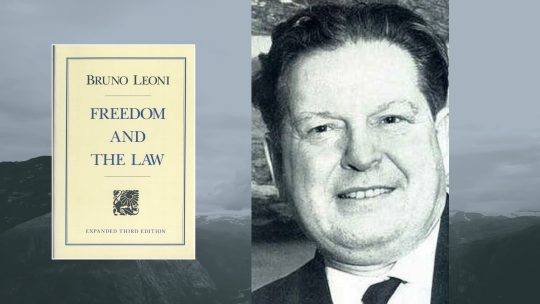

Dan Cristian Comănescu: Mrs. Greaves, it is a privilege for me to interview one of Ludwig von Mises’ outstanding American students. You attended Mises’ New York University graduate economic seminar for 18 successive years (1951-1969), and your two-volume Mises’ Annotated Bibliography (1993 [with Robert W. McGee], 1995) is, by now, a milestone of Austrian Economics. Let me begin with what Jacques Rueff once called “the intransigence of Ludwig von Mises”. Was Mises an intransigent man ? What about Mises the teacher?

Bettina Bien Greaves: Thank you, Cris for inviting me to discuss the late Professor Ludwig von Mises, his work, and the ideas of the Austrian school of economics, with which his name was closely associated for decades.

Yes, it is true. Mises was called “intransigent” by many — by friends as well as by enemies. In the standard English-language Webster dictionary, “intransigent” is defined as “refusing compromise, uncompromising, irreconcilable.” With respect to Mises, his friends would refine that definition. They would say he refused to compromise on what he considered to be true. He certainly was not a meek or docile person. He had the courage of his convictions and would not compromise principles. So we can call him “intransigent” for standing up for truth as he saw it. His enemies, those who could not accept his theories, would also call him “intransigent” but they would describe him as stubborn, obstinate, and even wrong.

How was Mises as a teacher? Economic theory, the principles of human action and the laws of praxeology that Mises presented in his seminar were developed through reason and logic on the basis of the indisputable fact that man acts. Presumably, no one who lives and breaths can deny that. Thus, anyone who wanted to argue with Mises would have to show that Mises had gone astray logically at some step along the way from his starting point, the a priori category of action. If Mises had reasoned incorrectly from the basic fact of action, then the economic theories derived from the fundamental of action would be wrong. But because he was so positive of the starting point, the fact that man acts, and that his reasoning was correct, it was very difficult to question him. Mises had a wealth of historical knowledge and frequently cited history to illustrate, not to prove, the theories he was expounding; the proof consisted of the logic. Students learned how to avoid having their arguments flatly rejected by Mises by asking him to comment on a recent newspaper article or some political proposal.

*

DCC: Let us return for a moment in 1931, when Mises could still write that the modern schools of economic thought “differ only in their mode of expressing the same fundamental idea and they are divided more by their terminology and by peculiarities of presentation than by the substance of their teachings”. Back then, however, Mises already stressed the superiority of the Austrian School in being able, for instance, to trace back the concept of cost “to subjective value judgements”. [Epistemological Problems, 1981, pp.165, 214] Please, explain in a few words the fundamental idea of modern subjective economics. Would it be correct to distinguish the Austrian School by its unique consistency in the development of that idea?

BBG: To answer your question, it might be well to compare the “Austrian” school with other schools of economics and explain why it is called “Austrian”. Before the 1870s, economists talked about prices and production, supply and demand, but they didn’t explain how prices came about, what determined production patterns or supply and demand. Adam Smith, who has been called the founder of “classical economics”, wrote that producers were guided by an “invisible hand”, but he didn’t explain that “invisible hand”. In the 1870s several economists, Carl Menger in Austria, Wm. Stanley Jevons in England, Leon Walras in Switzerland, and John Bates Clark in the United States pointed out the importance to economics of the subjective values of individuals. Ever since that time, subjectivism has pervaded economics, at least the micro- , if not the macro- aspects of economics.

It was Carl Menger in Austria who explained in greatest detail that prices, production patterns supply and demand, etc. all stem in the final analysis from the actions and preferences of individuals, each acting on the basis of personal subjective values and the closely-related marginal utility theory. The “school” that developed out of Menger’s teachings has been called “Austrian” because it was he and his Austrian successors who applied subjective value theory most consistently to all aspects of economics. Other economists tended to ignore subjective value when it came to macro-economic phenomena, i.e. the consequences of actions of many persons, groups, collectives, etc. The “austrians” pointed out, however, that even so-called macro-economic phenomena (production patterns, profits and losses, money, cyclical booms and busts, foreign exchange ratios, international balances of trade and payment, etc) are explainable only by recognizing that they are the outcomes of the actions and inter-actions of many individuals, each acting on the basis of his or her personal subjective values. Thus, subjective value theory, marginal utility, and individual actions are at the root of all, and I mean all, economic theories developed by the “Austrian” school. This gives the Austrians, as you say, “unique consistency in the development of that idea”. As its method stems from the actions of individuals, it is the school of methodological individualism.

When Mises wrote in 1931 that the Austrians not only clarified “the causal relationship between value and cost” but they also “ trace[d] back even this concept [of cost] to subjective value judgements”, [Epistemological Problems, 1981. pp.165, 214], he could not have anticipated the spread of Keynes’ ideas and aggregate economics. Even as late as the 1960s, Mises was writing that “after some years all the essential ideas of the Austrian School were by and large accepted as an integral part of economic theory. About the time of Menger’s demise (1921), one no longer distinguished between an Austrian School and other economics. The appellation ‘Austrian School’ became the name given to an important chapter of the history of economic thought: it was no longer the name of a specific sect with doctrines different from those held by others economists”. Thus it might be said that it vas the very success of positivism and Keynesian aggregate economics in overwhelming economic thought and gaining “mainstream” status that turned the Austrian school once more into “ a specific sect with doctrines different from those held by other economists”. [The Historical Setting of Austrian Schools of Economics, 1962/1969, p.41]

*

DCC. As early as 1944 Henry Hazlitt welcomed the Austrian challenge to the bureaucratization of the American mind, calling attention to “the ironic fact that the most eminent and uncompromising defenders of English liberty, and the system of free enterprise, which reached its highest development in America should now be two Austrian exiles” [Greaves & McGee Bibliography, p.93], Mises and Hayek. Would you agree to sketch, as a guideline for our readers, the fortunes of Austrian Economics on the American academic scene ?

BBG: It is difficult to trace the development and spread of ideas from person to person and from country to country. However, to answer your question, I shall attempt a brief explanation. The teachings of the Classical economists of the 18th and early 19th century — notably Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Ricardo — were superseded in the late 19th century by the development of subjective value theory and marginal utility. The economists who contributed to this advance in economic ideas were, for instance, Wm. Stanley Jevons and Alfred Marshall in England, John Bates Clark in the United States, Leon Walras in Switzerland, and Carl Menger in Austria. Jevons died not long after he published his book presenting the subjective value theory; the other men all failed to apply their value theory consistently to all economic transactions. For instance, Jevons and Walras tried to use statistics to describe value; Clark used it to support government intervention such as anti-trust legislation; and Marshall defended the welfare state philosophy by referring to marginal utility. Subjective value theory and marginal utility were defined more explicitly by Menger than by the other economists and he remained aloof from politics. Similarly his Austrian successors went on to apply Menger’s theories consistently to other fields of economics. Moreover, except for Böhm-Bawerk who served for a few years as Finance Minister, they remained in academia and did not take part in politics.

Prior to World War I, British and American economists had frquently done graduate work in Germany — J.B.Clark, for one, studied there. However, that practice died out with World War I, so few American economists after that knew German. Few “Austrian” school works were translated into English until after World War II, so they had little impact in the English-speaking world before then. At least very few British and Americans read them prior to the 1930s depression. Not understanding the cause of the depression, many people argued as a result that some sort of government action was necessary to prevent such economic booms and busts in the future.

Then the British economist, John Maynard Keynes burst on the scene. The depression had been widely blamed on the failure of free enterprise. Keynes held that the cause was a drop in consumer spending. To bring about recovery, to increase consumer spending, government should embark on a program of public works and subsidies, financed by inflation and credit expansion. Keynes’ explanation of the depression appealed to politicians and his program became the great model. Practically all countries in the world began huge spending programs. In the United States President Roosevelt introduced government spending through the New Deal. The subjective value theories as elaborated by the non-Austrians had not been thoroughly enough presented or consistently enough applied to resist the popularity of the Keynesian spending idea. Even university professors were attracted to Keynes. Therefore, as Hazlitt said in 1944, the two persons who defended “English liberty, and the system of free enterprise free markets” most convincingly were two Austrian exiles, Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek; neither had fallen under Keynes’ spell; both were outside of academia and the government bureaucracy.

*

DCC. Your late husband, Professor Percy L. Greaves, Jr., was a close collaborator and friend of Ludwig von Mises. In his 1973 book Understanding The Dollar Crisis, Professor Greaves described Milton Friedman, leader of the Chicago monetarist school, as essentially an “inflationist”. Why so ? If sound money is “the very essence of a market system” and inflation “the major economic problem of our century”, then is Professor Friedman not to be considered a free marketeer, after all ?

BBG: Milton Friedman has a delightful personality, is an excellent speaker and a skillful debater. He has been a popular teacher all his life. His lecture fees are phenomenal and in 1976 he received the Nobel prize in economics. He enjoys wealth, popularity, widespread acclaim and international recognition. Yet if a free marketer is one who understands market operations, how market prices are determined, their importance as guides to entrepreneurs and producers, and the need for a sound market-determined money to calculate how best to employ natural resources and factors of production to serve consumers, then Friedman cannot be considered a free marketer.

Friedman’s views on monetary policy reveal that he doesn’t understand money. For many years Friedman has held what the best, or he would say, the “least bad” monetary policy would be a law or constitutional amendment requiring the Fed, i.e., the U. S. government’s central bank, to increase the quantity of money at a regular, specified rate. He wants money to be increased just enough to compensate for the rising population and the increase in the production of goods and services. Friedman always emphasizes that any such increase in the number of dollars should not fluctuate erratically, but should be kept at a certain fixed, steady rate, for instance 3% or 4% per year. However, in advocating an increase in the number of dollars, he is recommending a policy of inflation, which is bound in time to bring uncertainty and the prospect of disaster.

Friedman further reveals that he doesn’t understand money, when he speaks of “money” as being government-issued paper currency, not money in the economic sense, i.e., the market-chosen medium of exchange. Today’s currencies are “derivatives”, one might say, of the sound gold and silver moneys that traders used to use. Government began by substituting paper notes and credit for the gold and silver. The next step was to declare these notes “legal tender”, compelling traders to accept them in trade. Then it withdrew the opportunity for people to use gold and silver in any transactions at all and left traders no choice but to use the government-issued paper. The departure from market-chosen money gives the government carte blanche power to manipulate the money, leaving the people completely at the mercy of government with no way to check government excesses.

Friedman reveals that he doesn’t understand inflation when he accepts the definition of inflation as rising prices. Actually, inflation is the monetary increase itself ; rising prices are simply one, perhaps the most visible, consequence of the monetary increase. Friedman reveals that he doesn’t understand prices when he announces that the goal of his monetary policy is to maintain “stable prices” and/or a “stable price level”. Apparently he believes that by increasing the quality of money at a steady rate, prices can be kept “stable”. But prices are never “stable”. The price tags we see on items in stores are “asking prices”; The price of a commodity when it is actually traded may be very different.

Actual prices are ephemeral, instantaneous exchange ratios between goods and services on the one hand and money on the other. They reflect the relative values of buyers and sellers, would-be buyers and would-be sellers, as they bid for the available supplies of goods and services on the one hand, on the other hand, for units of money. Every market price is a one-time affair, reflecting the value of particular market participants for a particular item at a particular time and place. Thus any change in the supply of any good or service and/or any shift in consumer demands, such as are ALWAYS taking place in this world of ours, lead inevitably to price changes. However, prices do not all change at the same time, to the same extent, or in the same direction. Therefore, to speak of “stable prices”, a “price level” or a “level of prices” is to say the least a poor metaphor; it is not even an accurate description.

In spite of Friedman’s failure to understand these important aspects of market operations, he talks like a free marketer when he criticizes big government, bureaucracy, subsidies, rules, regulations, and special privileges. He even criticizes the Fed’s inflationist monetary policy because it is erratic and unpredictable, because it does not follow his prescription for a steady rate. To Friedman’s credit, his criticism of government intervention is usually presented in such a delightful manner as to be persuasive even among government interventionists and advocates of the welfare state.

*

DCC: In recent years, classic liberalism has been increasingly associated with public choice analysis and constitutional economics. According to these schools a genuine program for prosperity should be encapsulated in an “Economic Bill of Rights,” a set of constitutional rules, such as The function of the Federal Reserve System is to maintain the value of the currency and establish a stable price level. If the price level either increases or decreases by more than 5 percent annually during two consecutive years, all Governors of the Federal Reserve System shall be required to submit their resignations. Of course, James D. Gwartney and Richard L. Stroup, who phrased this provision [What Everyone Should Know About Economics and Prosperity, 1993, p.108], would presumably recommend similar ones for adoption in the ex-communist countries, such as Romania. Is there any “Austrian” objection to this kind of scheme? Can you guess what Mises would have said?

BBG: First I should say that any attempt to stop or to slow down inflation should be applauded. However, I would criticize the Gwartney-Stroup proposal on essentially the same grounds as I criticized Friedman’s scheme. Gwartney and Stroup apparently believe, with Friedman, that it is desirable to increase the quantity of money and that such an inflationary policy could be consistent with a “stable price level”.

At the root of the disastrous monetary policies throughout the world is the widespread, almost universally-held BELIEF on the part of everyone — economists, government officials, businessmen, and public in general — that some inflation is actually desirable even necessary to assure economic prosperity and development. Inflation is absolutely NOT necessary! Moreover, rather than being advantageous it is disastrous!

In the 1953 epilogue to The Theory of Money and Credit, Mises offered his proposal for monetary reform. His goal was to find a way for a country to replace its inflated money based on credit expansion to sound money based on gold. The first step, he said, was to stop inflating! No new currency should be issued or new credit created by expansion. However, Mises did not recommend deflation or destruction of currency because of the serious disruption this would mean for existing monetary agreements.

Mises’ goal was to return gold money. To do that the market ratio between the nation’s monetary unit and gold would first have to be determined. Then people should be allowed to buy, sell and deal in gold. After some time the ratio between the monetary unit, the dollar for instance, and gold, would be determined. Then it could be announced that the dollar would henceforth be defined as that amount of gold. Market transactions could then proceed on that basis. Mises recognized that this was not a perfect scheme, but he considered it feasible and as good an arrangement as could be devised in our imperfect world.

One other problem I could have mentioned with reference to Friedman’s proposal, but didn’t, is also relative to the Gwartney-Stroup scheme. It would be difficult, I would say even impossible, to measure the percentage of the rate of the increase in prices. Price indices, aggregates, statistics, may give some rough indications of the extent to which paper and credit money have been increased over a period of time. But they are not exact or scientific measurements. Different statisticians will have different opinions as to what prices to include and how to weight the relative importance of different items. Trying to tie monetary policy to such a questionable guideline will never provide the central bank with a clear-cut guide to monetary policy.

From what I have read, it would seem that Romania might find it helpful to establish an advisory Currency Board. This Currency Board would have no actual connection with the money; its function would be simply to observe, advise, and help the central bank to curb its propensity to inflate. Countries that have had Currency Boards have found them generally helpful in curbing inflation.

*

DCC: This interview is meant to accompany a Romanian translation of Mises’ l959 Argentina lecture about “Socialism”. The late Professor Murray N. Rothbard, a brilliant American follower of Mises, once recalled his great teacher describing the existence of a stock market as the key to whether an economy was essentially “socialist” or a market economy [Review of Austrian Economics, Vol.5, No.2, p.59]. Please, explain this criterion. How is it related to the Misesian concept of a “mentally calculated division of labour between businessmen“ that keeps together the market system?

BBG: The possession of property, without the right to sell, is not true ownership; no one really owns something if he or she cannot use, dispose of it and/or sell it as he or she chooses. When companies and shares in companies are privately owned, they may be privately traded through a stock market; then neither owner nor potential buyer need ask permission of any Central Planning Office. Owners and potential buyers may buy and sell property, resources, tools, machines, and other factors of production, i.e. things needed to produce goods and services for consumers; they may trade, buy and sell, at their own discretion, all of their holdings or shares of their holdings whenever they agree on a price. Thus. the existence of a stock market, through which private individuals may buy and sell, is proof positive of a relatively free market and a private-property order.

Production is a cooperative effort; labor is divided among many individuals; none stands alone; all are independent. As owners trade with one another on a stock market in a private-property order, they divide among themselves the various operations of the market. Before deciding to trade, buy or sell, owners and would-be buyers try to anticipate whether a transaction will be worthwhile or not. They consider likely costs and the potential contribution to the market of each service or piece of property being offered. In this way, the values of the many services and shares of property are calculated mentally and integrated into the market system.

Buyers and sellers consider the potential market for the various goods or services under consideration; they look at costs of production, other items they could produce, other uses for their resources and other methods of production; and they bid for various factors of production. Through the stock market, owners compare the costs of different resources, the economies of other opportunities and productive processes. Prices evolve from the bids and offers of owners and would-be buyers. These prices provide information to traders. They serve as guidelines to consumer wants and technological changes, to the discovery and depletion of resources. Private resource owners use these prices as the basis for calculations. However, when governments own all the resources and a central planning office makes all the decisions, owners are not bidding for resources. So no prices develop. Without market prices to guide them the central planners cannot know what is going on, cannot keep abreast of consumer wants, methods of production or stocks of resources, and economic calculations become impossible. Unaware of changes, central planners tend to stick with their preconceived plans and do not adjust or adapt.

*

DCC: In his short masterpiece, Profit and Loss (1951), Mises wrote: “The fact that in the frame of the market economy entrepreneurial profit and loss are determined by arithmetical operations has misled many people. They fail to see that the essential items that enter into this calculation are estimates emanating from the entrepreneur’s specific understanding of the future state of the market” [Planning for Freedom, 1980, p.126]. Taking into full account this Misesian caveat, Professor Joseph T. Salerno contended that “socialism abolishes the quantitative appraisement of means without which man’s computational skills and his knowledge of particular facts and general technical rules would be completely useless in guiding production within the framework of the social division of labor” [Review of Austrian Economics, Vol.7, No.2, p.114]. Paradoxically enough, 70 years after Mises’ original demonstration, Professor Salerno’s restatement of the impossibility of socialism took by surprise quite a few Austrians, including, perhaps, Professor Rothbard who, in 1991, wrote: “I did not fully understand the vital importance of Mises’ s answer” about the stock-market as the key to a market-economy, until “recently, when poring over the great merits of the Misesian, as compared to the Hayekian, analysis of the socialist calculation problem.” [loc.cit.] What is so different about Professor Salerno’s restatement, as compared to the older, Hayekian ones?

BBG: One of the most important themes in Hayek’s writings was that information is widely dispersed in any society. His argument that central planners in a socialist society would not be able to calculate was based primarily on this diffusion of knowledge thesis. Information, he said, is known to countless widely scattered individuals, but much of it is not available to outside observers in books, reports, or studies; some of the widely scattered individuals possessing this information may not themselves even know what they know — for instance local conditions concerning undeveloped resources, soil fertility, consumer wants, preferences and values of consumers, ideas about innovations and changes that someone might conceive of and could make, and so on. Yet it is on the basis of such information that market prices are developed. No central planners, Hayek said, could possibly assemble the widely scattered data needed for the development of market prices.

People act on the market on the basis of such widely scattered data. As a result, market prices develop that reveal the relative supply of, and demand for, countless goods and services. A high price for something indicates scarcity and induces people to economize and/or expand its production; a low price sends a signal that that item may be used more lavishly. No central plan is needed as goods and services are “rationed” in this way on the market in response to the pricing system. Hayek’s thesis was that central planners, no matter how clever, could never assemble all the data needed to set such equilibrating market prices. In Hayek’s view, therefore, it is because of the diffusion of knowledge that a socialist economy could not function successfully. It is certainly true that the diffusion of knowledge makes the task of economic calculation difficult if not impossible for socialist planners but Mises goes one step farther.

Mises says that EVEN IF the central planners had available ALL the widely scattered knowledge needed concerning (1) supply, i.e. what resources were available and (2) demand, i.e. what consumers wanted and might want in the future, they still could not calculate — because there were be not prices. Prices evolve only in a free market society where goods and services are privately owned and where owners and potential buyers are free to buy, sell, bid, compete, and exchange with one another. For such a free market society to develop, it is essential that the factors of production, as well as consumption goods, be privately owned. But in a socialist society, the factors of production are owned and controlled by the government or some central authority. Therefore, in a socialist society, no buying, selling competing and/or exchanging takes place, in the true sense of the word, of privately owned goods. Hence, there can be no market prices in the socialist society. Thus the central planners will have no market prices to guide them and no way to know what to produce, how urgently, what quality, where, when, and how much.

Salerno’s interpretation is correct. When exchanges of privately-owned goods and services take place on the market, entrepreneurs analyze them quantitatively and qualitatively on the basis of “their specific understanding of the future state of the market”. Only as a consequence of the quantitative and qualitative analysis of entrepreneurs, in the light of their anticipation of future, do prices for various privately-owned factors of production evolve. From these market prices, entrepreneurs gain insight into the relative market values of various goods and services, making it possible for them to bring supply and demand more or less into balance. It is the absence of private ownership and of market prices, therefore, not simply the diffusion of knowledge, which makes economic calculation impossible under socialism.

*

DCC: The conventional homogenization of Mises and Hayek amounts to a watering-down of their specific contributions. I think this has been convincingly proved by Professor Salerno. In fact, Hayek himself admitted that while he found Mises “absolutely convincing in his conclusions” concerning socialism, he “never found Mises [calculation?] argument perfectly convincing.” [Bibliography, p.338] At a deeper, philosophical level, Hayek rejected Mises’ explanation of “social cooperation as an emanation of rationally recognized utility” and argued that “it certainly was not rational insight into its general benefits that led to the spreading of the market economy”. Then, Hayek went on to find excuses for Mises’s “extreme rationalism, …which as a child of his time he could not escape from” [Foreword to Mises’ Socialism, 1981, p.xxiii]. What is your position in this Hayek vs. Mises debate?

BBG: Personally, I do not believe Hayek rejected Mises’ position on the economic calculation debate as such. However, I believe he failed to appreciate it. Hayek did not seem to recognize the distinction between his “diffusion of knowledge” thesis and Mises’ position that the inability of socialists to calculate lay in the absence of private ownership and of market prices derived from the bidding among private owners. Even as late as 1992, Hayek failed to mention the role of private property ownership and gave the diffusion of knowledge and the absence of prices as the reason why socialist planners were unable to calculate: “[o]nce you begin to understand that prices are an instrument of communication and guidance which embody more information than we directly have, the whole idea that you can bring about the same order based on the division of labor by simple direction falls to the ground.” [Reason interview, quoted in my Mises Bibliography Update, p.190]

In my opinion the passage referring to Mises that you quote from the 1977 Hayek interview does not relate to the economic calculation debate but to Hayek’s rejection of Mises’ methodology, his epistemology. Hayek discussed his methodological difference with Mises also in 1978 at Hillsdale College. There Hayek criticized Mises for what Hayek saw as Mises’ “obscuring of the empirical fact” that people learn “what others do by a process of communication of knowledge”. (Imprims July 1978. See Greaves/McGee Mises: An Annotated Bibliography, pp. 341-342).

Mises never denied that people learn empirically and by communicating with others, and that they benefit from what they learn. However, for Mises knowledge of economics was not empirically-derived. For Mises, economics was the study of human action, choices, preferences. Mises started from the a priori fact that man acts and then used reason and logic to discover economic theories that explain the way man act.

Action itself, the impulse to act, Mises pointed out, springs from man’s innate nature. Man has unlimited wants but only limited resources. Thus, conflict between what man wants and what he has is inevitable. Man is driven to act out of a desire to relieve the uneasiness he feels due to his inability to satisfy his many wants with his limited resources. Empirically-derived knowledge may help him decide what actions to take and what means to use to attain various ends. But man acts and aims at ends not because of something he has learned empirically but because of his nature, because of the very natural human urge to try to relieve a felt uneasiness to satisfy his many wants with his limited resources. And we know a priori that man acts, not because we observe others acting, but because we are acting ourselves to attain various ends.

Hayek’s statement which you quote from the introduction to Socialism [Foreword to Mises’ Socialism, 1981, p.xxiii] is in my view another indication of Hayek’s methodological difference with Mises. Apparently Hayek could not accept Mises’ description of “all social cooperation as an emanation of rationally recognized utility”. Yet this statement is self-evident once one recognizes that the decision to cooperate begins with the idea that cooperation will improve the situation of those who cooperate. Anyone who participates voluntarily in a cooperative effort has made a conscious “rational” choice in the expectation that cooperation will yield “utility”, that it will improve his or her situation. And barring miscalculation, force, fraud, or threat thereof, voluntary cooperation does improve the situation of the participants.

Mises’ theory was one of methodological individualism. He viewed the market as the outcome of countless separate and cooperative actions, each stemming from the conscious voluntary decisions of individuals based on their considered judgement. The reason people first began to cooperate in ages past was because they expected cooperation would be helpful. And it was. So they continued to cooperate. All production and trade today is the result of interpersonal coopeation. And today’s market economy is an outcome of countless and widespread acts of cooperation.

Hayek argues, however, that “It certainly was not rational insight into its general [emphasis added] benefits that led to the spreading of the market economy”. Mises would certainly have agreed; acting men did not choose the market economy because they recognized its general benefits. Today’s market economy evolved out of the countless purposive actions and choices of individuals, each expecting some specific benefits from his or her action.

Hayek believed that “the thrust of Mises’ teaching is to show that we have not adopted freedom because we understood what benefits it would bring: that we have not designed, and certainly were not intelligent enough to design, the order which we now have learned partly to understand”. True to a certain extent. The relatively free market society we have today was not consciously chosen. Rather it evolved as a complex, interconnected network, out of the countless purposive separate and cooperative efforts of individuals. However, today’s social arrangements are not fixed and permanent; they are still evolving, in flux, changing from day to day. Thus, we are still bringing about changes in “the order which we now have”. If individuals are left free to enter into any voluntary arrangements they choose, the direction the economy takes in the future will tend to reflect their separate voluntary efforts to strive for specific benefits. Today’s economy, which reflects the actions and choices of everyone up to now, will be impacted by the actions and choices of individuals today, making tomorrow’s economy different from today’s. Because Mises believed that everyone tended to benefit when individuals were free to act and cooperate voluntarily, he opposed any course of action that would hinder the free decision and cooperation of thinking men. We cannot know what tomorrow’s economy will be, except that it will be different. And if the voluntary efforts of men are not hampered, it will be more beneficial than today’s.

*

DCC: Ever since Adam Smith, the “academically correct” reason for governmental activity – and the state’s power to tax – has been considered to be the “public goods argument”: the government is responsible for “erecting and maintaining those public institutions and those public works which, though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals, and which it therefore cannot be expected that any individual or small number of individuals should erect or maintain.” [The Wealth of Nations, Book 5,Ch.1] Smith includes here institutions and works “for the defense of society…for the administration of justice…for facilitating the commerce of the society, and those for promoting the instruction of the people”. Isn’t this kind of argument — grounded on the assumption of an external observer, measuring “social costs and benefits”– inconsistent with the modern theory of subjective utility? Did Mises ever evaluate it?

BBG: One argument for constructing certain “public works” is, as you mention, Adam Smith’s — namely that they are considered to be “in the highest degree advantageous to a great society” and yet “of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals.” However, this need not necessarily be true. Ronald H Coase, who was awarded the Nobel prize in economics in 1991, wrote a famous article in 1974, about lighthouses. He explained that even lighthouses, which most people would consider “in the highest degree advantageous to a great society” and yet “of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals,” could be operated privately for profit. He described the history of lighthouse operation during the 16th to 19th centuries when many lighthouses around the coasts of Great Britain were privately owned and operated.

They were financed by fees based on the size of a ship and the frequency of its visit in the vicinity of the various lighthouses. And quite some lighthouse owners made substantial profits. Coase concluded: “The account in this paper of the British lighthouse system does little more than reveal some of the possibilities. The early history shows that contrary to the belief of many economists, a lighthouse service can be provided by private enterprise. In those days, shipowners and shippers could petition the Crown to allow a private individual to construct a lighthouse and to levy a (specified) toll on ships benefiting from it. The lighthouses were built, operated, financed and owned by private individuals, who could sell the lighthouse or dispose of it by bequest. The role of the government was limited to the establishment and enforcemend of property rights in the lighthouse.”

There have been in the past and there still are many private toll roads and toll bridges, so it is not unrealistic to operate public works that are financed by user fees. Nowadays with so many new electronic devices, it is becoming easier to monitor automobile traffic, so that private highways and private bridges may become still more feasible.

But this doesn’t answer your question as to whether the reason why people ask for public works is “grounded on the assumption of an external observer, measuring ‘social costs and benefits’.” Perhaps! I can’t say.

Frankly, however, the question of government-constructed public works such as public highways, bridges dams, etc., does not disturb as me as much as do many other government activities if the government does not inflate or expand credit to pay for them. If the government doesn’t expand the quantity of money to finance a public project, the government must enter the market and compete like any other enterprise in buying resources and hiring workers. The government may be a very large and powerful buyer of goods and services but engaging in construction alone will not distort market activity. However, if the government inflates and/or expands credit to finance the construction of its public works, the situation is very different. The inflation and credit expansion will then distort prices and disturb the pattern of production throughout the economy. In Human Action (pp. 798-800) Mises criticizes proposals for the government to use public works for “contracyclical” purposes. In the attempt to counteract a business slow-down, it inflates or expands credit in order to embark on public works. The theory behind such schemes is that they will increase spending throughout the economy and perpetuate the monetary expansion boom. This is what Mises says about such a “contracyclical” policy: “The fundamental error of these projects consists in the fact that they ignore the shortage of capital goods ….. While the only real problem is to produce more and to consume less in order to increase the stock of capital goods available, the interventionists want to increase both consumption and investment. They want the government to embark upon projects which are unprofitable precisely because the factors of production needed for their execution must be withdrawn from other lines of employment [italics added]. ….They do not realize that such public works must considerably intensify the real evil, the shortage of capital goods”.(pp. 799-800)

You have a “beautiful” example of a huge government public works project in Bucharest. Ceausescu’s magnificent palace and parade ground deprived you people of Romania not only of funds but also of capital goods which certainly could have been used to better advantage elsewhere. It was probably paid for in part at least through monetary expansion which undoubtedly distorted production although the extent of the distortion is impossible to determine in a “planned” economy. It is apparent, however, through reduced productivity in Romania and lower standards of living for everybody.

*

DCC: In 1992 the Foundation for Economic Education published the first volume of its Freeman Classics, The Morality of Capitalism. Edited by Mark W. Hendrickson, it includes an adapted form (loosely speaking, the first part) of Mises’ Argentina lecture on “Socialism”. My question is: Can a consistent utilitarian and advocate of Wertfreiheit like Mises be legitimately be brought under the heading of ethics? At the bottom of this question is a long-debated concern of many Austrians: How can a value-free scientist and utilitarian liberal oppose any statist measure whatsoever, say the subsidization of farming or the murder of redheads, once it is supported by the majority and its economic consequences have been taken into full account?

BBG: Mises, as a utilitarian liberal, strove to be objective and to keep his science as logical and “value-free” as possible. The criterion by which he judged the morality or ethics of any action was not majority approval, however, but whether or not it promoted social harmony and peace. He believed that one did not need to look for a standard of morals to “eternal and absolute values and perennial justice”, which must always rest on fight. Mises also rejected natural rights and natural law as “quite arbitrary” and thus “not open to settlement”. [Human Action, p.720]. He held that the rationale for morality could be found in the field of human action itself. To decide what actions were ethically or morally “good” or “bad”, the only question to ask was whether it fostered, or hampered, social harmony: “There is …. no such thing as a perennial standard of what is just and what is unjust. Nature is alien to the idea of right and wrong. ‘Thou shalt not kill’ is certainly not part of natural law …. The notion of right and wrong is a human device, a utilitarian precept designed to make social cooperation under the division of labor possible. All moral rules and human laws are means for the realization of definite ends. There is no method available for the appreciation of their goodness or badness other than to scrutinize their usefulness for the attainment of the ends chosen and aimed at. …. The only standard for the appreciation of the laws and the methods for their enforcement is whether or not they are efficient in safeguarding the social order which it is desired to preserve” [p.720].

In order to determine whether an action helps or hinders peaceful social cooperation, one must use reason, logic and economic understanding. Let’s consider the two examples you cite — farm subsidies and murdering redheads, both of which appear to enjoy majority approval.

If the government subsidizes farmers, it must obtain the funds from somewhere, either from taxpayers or through monetary expansion. If the government levies taxes to get the money, taxpayers will then have less to spend on goods and services they would have preferred to buy. If the government inflates or expands credit to get the money, all prices and production will eventually be affected. True, the farmers may benefit, at least, in the short run. But their benefits must be weighed against the costs imposed on the taxpayers and consumers, who, unless the government subsidizes food purchases also, must pay higher prices for everything they eat. So to say that a majority favors subsidizing farmers is not enough to make utilitarians recommend it.

In an article in Planning for Freedom, “The Political Chances of Genuine Liberalism”, Mises discusses farm subsidies, with special reference to sugar: “The immense majority of the American voters are buyers and consumers, not producers and sellers of sugar. Nonetheless the American Government is firmly committed to a policy of high sugar prices by rigorously restricting both the importation of sugar from abroad and domestic production. Similar policies are adopted with regard to the prices of bread, meat, butter, eggs, potatoes, cotton and many other agricultural products. … Less than one fifth of the United States’ total population are dependent upon agriculture for a living.[…] Conditions being such, the prospects for a genuinely liberal revival may appear propitious. At least fifty per cent of the voters are women, most of them housewives or prospective housewives. To the common sense of these women a program of low prices will make a strong appeal. They will certainly cast their ballot for candidates who proclaim: Do away peremptorily with all policies and measures destined to enhance prices above the height of the unhampered market!… What we want is low prices.”

Subsidies also have other side effects of which utilitarians cannot approve. By granting benefits to farmers at the expense of others, they create resentment among taxpayers and consumers that is not conductive to social cooperation. Thus utilitarians argue against farm subsidies as well as any all other government programs, even though they may have majority support, because they are disruptive of peaceful social cooperation.

A policy of murdering redheads would be still more disruptive of social harmony than farm subsidies. All redheads would object vigorously, also relatives and friends of redheads. Other groups might also fear that they might be the next group targeted for being killed. The Protestant theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was imprisoned by the Nazis and died in one of Hitler’s concentration camps toward the end of World War II, has been quoted more or less as follows: “First they came for the Jews, and I was not a Jew so I didn’t protest. Then they came for the professors, and I wasn’t a professor so I didn’t protest. Then they came for the profiteers and I wasn’t a profiteer so I didn’t protest. Then they came for me. And alas there was no one left to protest”.

Utilitarians, including Mises of course, advocate tolerance for different ideas: they favor a free press, freedom of speech and the right of everyone to express his opinion, so long as they do not use force or advocate the use of force to impose their opinions on others. Toleration for different opinions, of course, does not imply approval. In this vein, the famous French philosopher, Voltaire, is reputed to have said: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”. It is only by tolerating differences of opinion that many people with different religions, philosophies, goals and values may live together and trade with one another in peace.

*

DCC: Ludwig von Mises certainly was no apologist of the American economic policies. “One of the privileges of a rich man – he said – is that he can afford to be foolish much longer than a poor man.” [Economic Policy, 1979, p.72] Following your great teacher’s example, you talked last year in Eastern Europe about “what people living in the formerly communist countries could learn from the U.S., and what they should not learn from the U.S.” Would you accept to summarize your message, for our readers?

BBG: In this world of ours, nothing is free; we must labor to obtain the basic necessities of life. It was even decreed in the Bible that men must work: “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread”. (Genesis 3: 19) While the poor man must work everyday to keep a roof over his head and to produce the daily bread for himself and his family, the rich man who owns property and has stocks of food on hand doesn’t need to work regularly; he can relax and waste his wealth, at least as long as it lasts. Thus, as Mises said, the rich man can afford to be foolish longer than the poor man. If this seems unfair, remember that, unless the rich man stole his wealth, received gifts, or was given some special privilege by king or government officials, he also acquired his wealth by working. However, he did not immediately consume all he produced but set some aside as we say, “for a rainy day’’ or for some other unexpected and perhaps unfortunate eventuality.

We envy the rich man, his wealth, and the freedom it gives him to be foolish, to relax and enjoy life. Just as the poor man envies the rich man and asks how he too can acquire such wealth, so too do poor countries envy rich countries and try to emulate them. Today, the United States is rich as compared with most other countries. Therefore the citizens of other countries would like their governments to follow the example of the United States so as to become rich. Fine! But they should make sure that they adopt the policies that enabled the people of United States to become rich. Not the “foolish” polices the United States government has been adopting since it became “rich” and could “afford to be foolish”.

In the beginning, of course, the United States wasn’t rich. The people had to work hard to produce food, move goods from one place to another, lay out roads, construct factories, and build ships as did the inhabitants of other poor countries of that day. Let us consider, for instance, the situation in the United States from the time when it declared its independence from England (1776) until the start of World War I (1914). During this period, the government interfered very little with the activities of private individuals. The people were on their own, free to pursue whatever activities they chose. They were completely responsible for themselves and their families. Thus they had a strong incentive to do their best. No one told them what to do, where to live or where to work. Acting alone or in cooperation with others they grew their own food, built their own homes, educated their own children and, except for occasional help from family members or friends, they took care of themselves and their families in sickness and old age.

During those years, the people of the United States accomplished a great deal! They brought vast new lands under cultivation, developed new methods of transportation and communication (steamships, railroads, telegraph, telephone), improved agricultural methods, opened large coal and iron mines, built many factories and established trade routes around the world. They improved production methods and increased production, but they did not consume all they produced. They saved something. With more savings, they could afford to devote some time and resources to developing more tools, machines and factories. These new tools machines and factories made it possible to increase the production of consumers goods still more. And so they saved more and expanded production still further.

Before World War I, the United States government interfered very little in the private affairs of its citizens, so long as they did not use force or fraud against others. Government didn’t need much money because its activities were limited primarily to the protection of life and property against domestic and foreign aggressors. So taxes were low. Because of government’s “hands-off” policy and low taxes, people were free from government interference, And they put forth prodigious effort to produce and save more because they were responsible for themselves. The work, production and savings of our 19th century contributed substantially to the wealth of the United States in 20th century.

By the end of World War I, the United States had become the most wealthy and most powerful country in the world. Generally speaking, however, since then the United States government has adopted a different philosophy. Because it had become “rich”, it could afford “foolish” policies that were expensive, even destructive of productive effort. In 1913, it established the Federal Reserve Bank, modeled after “central banks” of many European nations. The Federal Reserve opened the door to the manipulation of the quantity of money and credit, leading to the 1920th “boom”, the 1929 stock market crash, and the widespread economic depression that followed. In the early 1930s, just before Republican President Hoover left office, it began a program intended to hold up prices and wages artificially; it granted subsidies to farmers and some businesses. After the new Democratic President Roosevelt took office in early 1933, government interventions proliferated. The United States government adopted a social security system, modeled after Bismarck’s program of the 1890s in Germany. It enacted laws giving privileges to labor unions, to the disadvantage of non-union workers. And it began building high-rise public housing, constructed public works projects, including huge hydro-electric power dams, built hospitals, and subsidized the local public schools. It also embarked on a policy of inflation, expanding the quantity of money ostensibly to maintain “full employment” by government spending.

Such interventionist government programs are not only costly; they are also “foolish”. They destroy the incentive of everyone — workers, producers, entrepreneurs, savers, investors, taxpayers. Why put forth so much effort to work, save and invest, if the government will help pay for housing, schooling, medical care, hospitalization, old age insurance, etc.? Why work so hard to produce, save, invest, if your earnings are to be heavily taxed to care of the less industrious and less provident?

Countries seeking to become rich would do well to adopt the policy of limiting government that enabled the United States to become rich. When the government of the United States was limited to protecting the lives and property of all citizens from domestic and foreign aggression, its goal was to treat all citizens equally under law: no one should receive special privileges. Every one should be protected equally without prejudice or favor to anyone. Countries seeking to become rich, should not try to model themselves on the basis of the “foolish” programs the United States has adopted in recent decades, programs that are wasting resources and destroying the incentive of workers and producers. The 19h century French journalist and Deputy Frederic Bastiat described such government programs that took wealth from some for benefit of others as “legal plunder”. “The State”, he wrote “is the great fiction through which everybody endeavors to live at the expense of everybody”.

Instead of taking the responsibility for their own family’s housing, health, education, and welfare, many U.S. citizens now expect the State to pay. And in that direction lies disaster, not only because it destroys the incentive of non-workers to seek work but also because it discourages the most industrious workers from doing their utmost to produce. The United States is still a relatively rich nation and can afford to be somewhat “foolish”. But poor nations seeking to become rich should emulate the polices that enabled the United States to become rich, not by copying those “foolish” programs that are now wasting its wealth.

*

DCC: In a bitter appendix to his book on Liberalism (1927), Mises wrote: “Hardly a breath of the liberal spirit has ever reached the peoples of eastern Europe”. Unfortunately, one “may not make the way to liberal thinking easier for anyone, for what is of importance is not that men declare themselves liberals, but that they become liberals and act as liberals.”[1985, pp.196, 200] How would you describe the present state of the “liberal spirit” in eastern Europe, after your visit of Romania and a few other ex-communist countries ?

BBG: It is difficult for anyone who does not know the language and cannot talk to the “man of the street” or read the press, to describe the “spirit” of a people after visiting a country only briefly. However it seemed me that a “liberal spirit” was reviving in Warsaw (Poland) and in Moscow (Russia). By the time I was there, October 1994, many individuals in those cities had opened small private shops on the busy streets; foreign companies apparently considered the economic climate there suitable for investment, for stores were stocked with imported items; and foreign products were widely advertised on billboards. However, Romania seemed to be less fortunate; she had not succeeded in throwing off the Communist yoke as soon as had the other countries. And associates of Ceausescu remained in power. Thus, a revival of the entrepreneurial spirit seemed to have been delayed in Romania. However, from what you told me, some people were beginning to show more initiative and effort than before Ceausescu’s downfall. You said the food markets and small shops were better supplied than they had been before.

Budapest (Hungary) and Prague (Czech Republic) were not damaged so much during World War II and their streets and buildings were in relatively good repair. Their shops were quite modern and seemed to be prospering. Because inflation is such a recent memory in Hungary, people are fleeing into real values, sparking an artificial building boom by buying real estate and building houses in the hope of salvaging some of their asserts from thr ravages of inflation. In the Czech Republic about 80% of formerly government-owned companies has now been successfully privatized.

It is difficult to destroy completely the entrepreneurial spirit, and I saw signs of its revival in all the countries I visited in eastern Europe. However, most people still look to government, as people do to a considerable extent here in the United States also, to guarantee employment and to provide housing, security, medical care, etc.

The natural tendency among individuals to cooperate and trade with another holds out hope everywhere for the future of freedom If this natural drive, this inborn characteristic, is not hampered, people will find some means to communicate and exchange with another, All that government need do is to refrain from interfering. If people are not actively prevented from trying to pursue their own personal goals, if they are free to act as they choose so long as they do not interfere with the equal freedom of others, if they may own property and use it as they wish, their actions will lead in time to peaceful intercourse, exchange and markets.

* * *

A Romanian translation of the questions and answers above were published in the June & July 1995 issues of the Alternativa political supplement to the a well known Romanian daily newspaper (Cotidianul), along with Comănescu’s translations of Mises’ 1959 Argentina lectures on “Socialism” and “Interventionism”, as a two-part interview.

© 2002 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute – Romania